Reconciling Libertarianism and zoning ... and a sketch of a Pareto-efficient transition to a free-market alternative

Part 1 of 3

(Part 2 can be found here, and part 3 here)

“The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath” - Mark 2:27

An introduction to zoning

"Zoning" is the term for a type of legislation or regulation that sets up geographical zones, and limits how land in each district can be used. Technically, the term refers to a subset of "land use laws", and only actually describes laws that divide land up into these zones, but the term has evolved into a bit of a metonym, so in the vernacular it stands for the entirety of land use laws.

Zoning and land-use laws in the US are commonly said to date to the early 20th century, when - in the popular narrative - they were brought about by good progressives doing good progressive things (like banning alcohol, regulating railroads, destroying affordable housing ("slum clearance"), etc.)

The conventional narrative

The progressive stance on land-use law has been - until very recently - that it is absolutely necessary to coordinate diverse selfish interests each of which - left to their own devices - would engage in negative-externality behavior.

The conventional libertarian stance on land-use law has been "my land is my land and I have an absolute right to do whatever I want on it, and that includes running a 24 hour strip club / bar even if that's next to a church or elementary school or a gasoline distillation plant, even if that's next to an orphan's home.

The progressive stance has recently changed, because after only 100 or so years of conservatives explaining that excess regulations increase costs and reduce supply, leftists have discovered a new truth: excess regulations increase costs [ on the working poor, who we care about ] and reduce supply [ of housing in walkable neighborhoods with bodegas and coffee shops, which we care about ].

In some places (e.g. the New Hampshire statehouse) there is a new progressive/libertarian alliance, which aims to do a good thing (reduce burdensome regulations) in the absolutely worst way possible ( reducing citizen access to due process laws in a way that empowers defectors and recent arrivals to profit while externalizing most of the costs onto people who have engaged in pro-social behavior (invested time, effort, and money in making nice places).

Reform - of a very new and weird type

In this essay I suggest that the goal is good, the proposed reforms are terrible, and there is a much much better approach that is not only better in the steady-state (once achieved), but has a hugely more moral in that the transition does not deal out random and arbitrary damage to people who were engaged in rational and pro-social behaviors.

A longer history of land use law

The reality is that the early 20th century is merely the time when American land use law started getting more detailed and formalized. In fact, land use laws existed before that, under the common law doctrine of "nuisance", which says that activities that person A do on their own property can so impact the use and enjoyment of person B to his nearby property that they are a violation of person B's property rights.

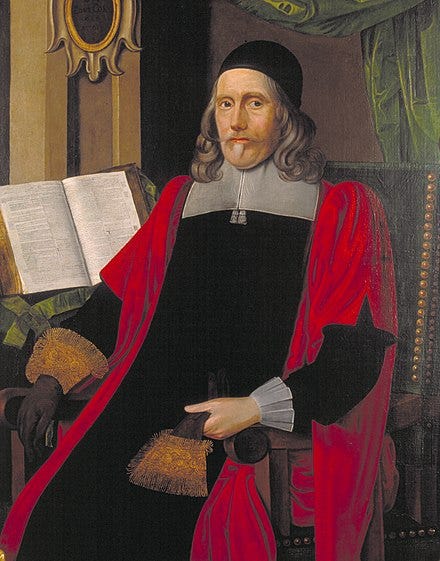

The doctrine of nuisance dates at least as far back as 1610, to "William Aldred's Case", which comes down to us in "The Reports of Sir Edward Coke", a compendium of legal writings of - wait for it - Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634), a contemporary and political rival of Francis Bacon.

Coke introduced the Aldred case as follows:

William Aldred brought an action on the case against Thomas Benton, which began 29 Septemb' anno 6 Jac. [ September 29th, in the sixth year of the reign of King James, i.e. 1608 ]

An action on the case lies for erecting a hogstye so near the house of the plantiff that the air thereof was corrupted. (so of a lime-kiln, if the smoke enteres the platiff's house, so that he cannot dwell there, so of a dye-house, &c. if the filth runs into his fish pond, &c.)

And explains, in Latin:

tam prope aulam et conclave ipsius Willielmi, ac sues et porcos suos in aedificio illo posuit, et ill' ibid' per magnum tempus custodivit, ita quod faetidi et insalubres odores sordidorum praed' suum et porcorum praed' Thomae in aulam, &c. penetran' et influen', idem Willielmus ac famuli sui, &c. in messuag' praedict' conversantes existentes absque periculo infectionis in aula, &c. continuare seu remanere non potuerunt, pretextu cujus idem Will to-tum commodum, &c. maximae partis praedict' messuag' per totum tempus praed' totaliter perdidit. "

or, in English:

"so close to the hall and chamber of the said William, and he placed his pigs and swine in that building, and kept them there for a long time, so that the foul and unhealthy odors of the said pigs and swine of Thomas penetrated and flowed into the hall, etc., such that the same William and his servants, etc., dwelling in the said messuage could not continue or remain in the hall, etc., without danger of infection, by reason of which the same William entirely lost all the benefit, etc., of the greater part of the said messuage for the whole time aforesaid."

The cases concluded with the judgement that a man has

"no right to maintain a structure upon his own land, which, by reason of disgusting smells, loud or unusual noises, thick smoke, noxious vapours, the jarring of machinery, or the unwarrantable collection of flies, renders the occupancy of adjoining property dangerous, intolerable, or even uncomfortable to its tenants."

This may be the earliest documentation of Anglo-American land use regulations we have easy access to, but this hardly the earliest example of land-use regulations in the West - they go much further back!

Under the Roman Republic (509 BC - 27 BC) there were a variety of laws that correspond to our formal concept of zoning or land use regulations (maximum building heights, setbacks, exiling noxious trades such as leather making to beyond the city walls, etc.), and also to our common law concept of nuisance - forbidding degrading a neighbor's experience of his own property.

England and Rome are not unique in these regards - every society that we know of had certain land use regulations.

(Some people will counter that Rome law explicitly enthroned the concept of "dominus", which was complete and utter ownership of property or a household - the Latin root of our English word "dominate", and the child of the Latin word "domus" which gives us the English "domicile". Roman law did not actually implement "dominus" in practice, but used it as the sort of Platonic ideal of what absolute property rights might look like ... before they were constrained by other legal principles.)

The game theory of land use

The point of diving into the history on land use laws is that people have always and everywhere, when they've come together and lived near each other, had legitimate concerns about actions that others near them will take.

Why?

Because there is an asymmetry in the universe: it is much harder to build something than it is to ruin something that has been built. To build a thing, 100 or 10,000 or 100 million parts must be crafted, brought together, and assembled.

To ruin something, only one or two things have to be disturbed.

It takes much more effort to create a cask of fine wine than it does to stir a teaspoon of feces into it.

It takes much more effort to build a firm over generations than it does to bet it all on a highly leveraged investment, or a horse race.

It takes much more effort to create a space shuttle than it does to launch in cold weather with a frozen O-ring.

People are naturally loss-averse, when it comes to their own assets, because they know how hard it is to acquire them and build them.

It is thus inherent in human nature to want to preserve what one has built.

If one has build a delightful family home over twenty years, one has a legitimate, very human desire to stop a 24x7 liquor store from opening next door.

Which leads us to ...

The naive libertarian take on property rights

There is an eighth-grade libertarian take on property rights: "it's my land, and no one has any right what-so-ever to limit absolutely anything I do on it".

There is an 11-th grade cognate of this take, that adds in specifiers: "all the way to the center of the Earth, and as far up as I can see."

Amusingly, high school libertarians thus often reinvent the legal principle of "Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos" (Latin for "the soil belongs to the owner, up to Heaven and down to Hell").

This formulation, by the way, dates to almost exactly the same era as the Aldred case.

What are we to make of the libertarian definition of property rights?

First, let me set the stage:

I consider myself a libertarian. I consider individual rights, including extremely extremely strong property rights, to be the most important pillar that a society should be built on, and the most important criteria on which we should judge the legitimacy of a state.

I explain this so that my criticisms of this formulation of property rights will be taken as a criticism of this formulation, and not of property rights.

(The immediate response to that is "Yeah, well, I've heard progressives say that they're in favor of 'free speech', but then define 'hate speech' as being outside the boundaries of legitimate speech, so, Travis, merely claiming that you're in favor of property rights is not sufficient to dispel my distrust - you talk like a fag, and your shit's communist."

Good!

Keep that skepticism!

The burden of proof is on me to convince you otherwise.)

When naive libertarians argue against any sort of restrictions on land use, the debate normally plays out like this:

sane person:"I've spent 20 years building a very nice home. If we get rid of land use laws, and you move in next door, what happens if you pile up a dozen broken cars in my front yard?"

naive libertarian: You should get shades for your windows.

sane person: "and if you shine a light in my window?"

naive libertarian: dark shades.

sane person: "what if that light is a laser, and it burns my shades?"

naive libertarian: that would be a violation of the NAP [ Non Aggression Principle ], because in that case I’ve caused physical changes on my property, and you could call the police.

sane person: "what if you set up loudspeakers in your front yard?"

naive libertarian: that's my right, as long as I'm not touching your land.

sane person: "doesn't the sound cross over the boundary?"

naive libertarian: yes, but my speakers don't cross the boundary, so it's OK.

sane person: "You assert that you have a right to buy that lot next door and set up a brewery if you want, right?"

naive libertarian: yes

sane person: “What if odors drift over?"

naive libertarian: That wouldn't be my direct doing; the wind is to blame. So that's just a problem you have to deal with.

sane person: "what if instead of a brewery you set up a chemical plant?"

naive libertarian: if the smells were sufficiently bad, then that would violate the NAP.

sane person: "how would we determine 'sufficiently bad' ?"

naive libertarian: [ thinking hard ] it would be a 'tort', which means that you could sue me.

sane person: "how much would that cost?"

naive libertarian: I don't know.

sane person: "and if I won, what then?"

naive libertarian: Then I'd have to stop.

sane person: "ok, so it's your right to build a chemical plant and emit terrible smells, and if I dislike that, I'd have to spend $25,000 to sue you, and each such lawsuit would be decided case-by-case by an unelected government employee, and - after five or six years of litigation - if I won, you'd stop emitting the smells, but if I didn't win, you wouldn't - and in either case, I'd be out of pocket $25,000?"

naive libertarian: yes, exactly!

sane person: "And you want this system instead of a land-use law that merely says 'you can't build chemical factories in residential neighborhoods'. Why?"

naive libertarian: Because this would better than the current system!

My brother in land-use law, this is a better (and by "better" I mean "more retarded") joke than "The Aristocrats".

If you find yourself ever making an argument this dumb, or allying with people who make arguments this dumb, that should be a serious piece of information that should update your Bayesian prior on "are we the baddies?"

Mark 2:27 reads

The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath

which conveys the message that the Law is intended to benefit people; the goal of it is not to have people contort themselves to deal with the demands of an ill-fitting system.

The various libertarian proposals about land use ("what do you care if I set up a 24 hour casino next to your house; just move!", "so sue me", etc.) present a deeply autistic model of what land use "should be" that does not fit what people actually want from land use law, and they provide no justification for their system being superior to alternative systems other than "it's crisply defined in terms of the NAP".

Let's pretend that it is (it's not): ok, fine. "Crisply defined in terms of the NAP" is not a virtue if we're shopping for a couch, or a bed...or anything else designed for human use.

What's wrong with the libertarian proposal?

The naive libertarian proposal to replace land use laws with torts fails in a variety of ways, but it mostly boils down to three:

It has no prospective rules. Prospective rules are good because they let people proceed with certainty, and certainty encourages economic activity at both the large scale (building factories) and at the small scale (building a chicken coop).

It depends on retrospective enforcement (torts), and torts are exceedingly expensive to prosecute. By the time you've done interrogatories, $25,000 is a reasonable average cost to try to litigate a dispute.

The incentives are bad: the richer party can bully a less-rich party because the rich party is more able to fund law-fare the predictability of any given ruling is low.

The system depends on conflict - which has side effects like poisoning relationships.

Ok, Travis, if the current system is bad, and libertarian proposals are worse, what's your great idea?

I'll answer that, but first we have to back up and discuss...

What is property ?

Property, in Anglo-American law (and in this essay) is:

the right to use a thing the right to earn income from the thing the right to transfer the thing to others, alter it, abandon it, or destroy it

The debate around "is any zoning / land-use regulation ever legitimate?" normally centers on the first bullet point: may the state morally/legitimately forbid a person from doing what he wants with his own good?

I believe that that debate is poorly formulated, occurs on the wrong ground, and leads zero-sum thinking, and in turn to shouting "does" / "does not" / "DOES!" / "DOES NOT!!!".

We need to reformulate the debate

I want to reformulate the debate.

My stance is:

the state may NOT morally/legitimately forbid a person from doing what he wants with his own good (the normal libertarian point)

...but there is a conceptual problem where naive libertarians misunderstand what property they and others should (and actually do) own and we should strive to formalize this implicit reality, and bring more market mechanisms to bear on it.

By accepting these two assertions, and looking at the implications, we can, I assert, square the circle and create a land use system that gives everyone exactly what they want.

In parts 2 and 3 of this essay I'll explain exactly how I propose to do that.

( Don’t worry, I won’t hide the punchline way at the end - I’ll start off part 2 with a bang, by explaining exactly what resolution I propose. )

Somehow missed this when it was published. Just finished part 1 and subscribed. Now onto part 2!

OMG I’ve been dying to finally read your long-form commentary on this. Sane land-use reform is the key to sanity in the liberty movement.